Journey into rust #1: Conway’s Game

Rust has been popping up on my twitter feed more and more. It’s been promoted and presented as the ultra safe language, so naturally I decided to check it out. The upcoming series of posts “Journey into rust” will describe and document my experiences using rust, hopefully explaining certain concepts that rust does differently. This will all be written from a C++ programmers standpoint that was thought writing Object Oriented code. I encourage you the reader to think critically and correct where necessary.

On to the actual first post! After reading “the Rust Programming Language” I wanted to get my hands dirty and actually write some code. I like graphical applications and using low level graphics API’s so I decided to implement a cellular automation in rust. But just implementing cellular automation isn’t very exciting, is it? What if we could do this on the GPU…And off I went on my journey to create Conway’s game of life in rust.

Rust has several “crates”, a library bundled for ease of use, that we could use for that. I’ve chosen for gl and glfw. Note that the gl crate merely provides “unsafe” bindings to opengl but I wouldn’t be a real C++ programmer if I didn’t like a bit of “un-safety”! All jokes aside, I implemented a small type based wrapper around most commenly used constructs (Shader programs, meshes and so on). All these constructs will be prefixed with “glw::” or there will be “use” declarations importing the definitions.

Conway’s game of life

“The Game of Life, also known simply as Life, is a cellular automaton devised by the British mathematician John Horton Conway in 1970.” ~ Wikipedia

A cellular automation is some sort of evolution loop where each next state depends on what the previous state was. In the game of life this is done in a grid, as each cell examines it’s 8 neighbours to determine it’s state.

If you aren’t familiar with the game of life or cellular automation I encourage to check out the wikipedia page!

Below you can see the final result of this article.

Implementing the algorithm

In this post I won’t go over the specifics of creating and opening a window in rust as that is not my goal. All the sample code can be found on my github, feel free to browse and ask questions about it.

Breaking down the problem

The way to go about implementing something like this is to break this down on paper first, ignoring the details of the API’s. A cellular automation is some kind of evolution, each cell has a certain state every cycle. This state depends on the previous evolution that was made. In our case the first evolution is special and randomly generated.

If we were doing this on the CPU we could create a grid using the Vec<T> type that the standard library of rust provides. However, we want to do our evolution on the GPU ( very fast :) ). Hmmm, so we want a 2D array that stores data about whether a cell is alive or dead… That sounds like a perfect job for textures!

Generating the initial state

So randomly generating our first evolution would mean randomly filling in our texture with either black or white. In our case I chose for a RGBA8 texture to keep things simple but in reality a single channel texture would have sufficed for the purpose we are using it for. And technically we only need 2 possible values, 0 and 1! But using colours makes it easier to visually output the evolution.

fn generate_field(field_size: &Vec2<i32>) -> Vec<Color> {

let mut rng = std::rand::thread_rng();

let mut image = Vec::new();

for _ in 0..field_size.x*field_size.y

{

if rng.gen::<f32>() > 0.1 {

image.push(Color::new(0,0,0,255));

}

else

{

image.push(Color::new(255,255,255,255));

}

}

image

}Evolving our cells

Now that we have our initial state we need to “evolve” it in some way. On the CPU this would be done by looping over each and every pixel and checking it’s neighbours to figure out if the next evolution is alive or not. The result is then stored into an equal sized buffer.

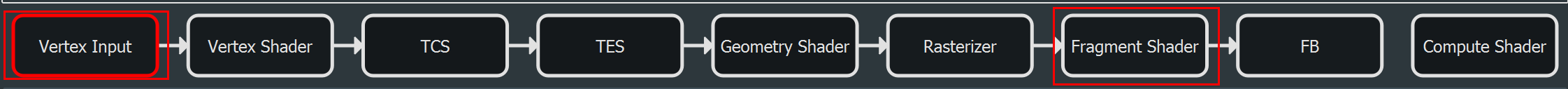

A nice thing about GPU’s are that we can execute shader programs on them. If you want to understand more about graphics pipelines in general I recommend reading open.gl although I will try my best to give a brief overview of what a shader program can do. When drawing meshes to the screen with the GPU the mesh data has to go through the graphics pipeline. The graphics pipeline consists of different stages the stages that we are interested in is the “vertex shader” stage and the “fragment shader” also known as “pixel shader” stage.

Vertex shader

A vertex shader runs for each vertex in mesh, this is useful to apply transformations to a mesh to render it in different positions (and so much more). The only reason our program uses a vertex shader is to pass through a quad mesh to the next stage (“fragment”). The values that pass through shader programs and end up in the fragment shaders stage automatically get interpolated ( see “rasterization” ) Note: In reality there are a bunch of other stages between the vertex and fragment stage but we can safely ignore them for now.

Our vertex shader is rather simple:

#version 440 core

layout (location = 0) in vec3 aPos;

layout (location = 1) in vec2 aUV;

layout (location = 0) out vec2 oUV;

void main() {

gl_Position = vec4(aPos.x, aPos.y, aPos.z, 1.0);

oUV = aUV;

}gl_Position is a buildin variable that should contain the position of the current vertex. Read more…

Fragment shader

The real logic will happen in a fragment shader, this program is executed per pixel. Meaning this is perfect to sample the neighbouring pixels and calculate the next state, below is a somewhat crude implementation of described logic.

Some things to note:

- texture() reads a pixel using a specified uv coordinate (0-1 where 0 is the left of our texture and 1 the right).

- textureOffset()reads a pixel using a uv coordinate and an absolute pixel offset specified, perfect for us

- we only read the red channel from a cell to determine if they are alive or dead.

float curr = texture(u_texture,uv).r;

bool alive = curr > 0;

int count = 0;

for(int i = -1; i <= 1; ++i)

{

for(int j = -1; j <= 1; ++j)

{

if(i == 0 && j == 0)

continue;

float tex = textureOffset(u_texture,uv,ivec2(i,j)).r;

if(tex > 0)

++count;

}

}

float new_cell = curr;

if(count < 2) new_cell = 0.0f;

else if(alive && (count == 2 || count == 3)) new_cell = 1.0f;

else if(alive && count > 3) new_cell = 0.0f;

else if(!alive && count == 3) new_cell = 1.0f;

FragColor = vec4(new_cell,new_cell,new_cell,1.0f);What we would get with this program when rendering:

Rendering loop

For this part I’ve written quite a lot of abstractions to wrap around the “unsafe” gl code. Which is found here! There’s 3 stages in our rendering loop:

- render the next grid state using our shader program

- copy over the next state to a intermediate render target to use as input for the previous state in the next cycle.

- render the next grid state to our FB0, screen frame buffer

I’ve omitted some of the external details such as clearing the framebuffer and setting up a viewport etc.

ctx.bind_rt(): Binds a render target (texture) to draw to

ctx.bind_pipeline(): Binds a Graphics pipeline object, which is a collection of shader programs

set_uniform(): Set’s the input uniform (“GLSL variable”) to the previous state texture

Stage 1: Rendering Game of life

ctx.bind_rt(&self.fb_curr_state);

ctx.bind_pipeline(&self.render_quad_prog);

self.render_quad_prog.set_uniform("u_texture",Uniform::Sampler2D(self.fb_prev_state.get_texture()));

self.draw_quad();Stage 2: Copying over for next cycle

self.gl_ctx.bind_rt(&self.fb_prev_state);

ctx.bind_pipeline(&self.composite_quad_prog);

self.composite_quad_prog.set_uniform("u_texture",Uniform::Sampler2D(self.fb_curr_state.get_texture()));

self.draw_quad();Stage 3: Rendering to framebuffer

This is the same code as stage 2, but instead of binding a render target that we created earlier in the program we will bind to a “default” render target, which internally binds framebuffer 0, in opengl this means that we will be drawing directly to the screen.

This code is available directly on github: here

Conclusion

It was quite interesting to try this out and experience all the rust it’s roadblocks and it’s trigger happy compiler although I think I will keep using rust to experiment and create smaller projects. Now that I’ve already build a smaller library/crate of utilities when writing the game of life I feel more confident.

There’s definitely areas to improve upon in the application but I will leave this to the reader, or if I ever revisit this I will update the repository! Hope you enjoyed this first “real” article of me on how to render the game of life using a GPU for the evolution.

References

- Wikipedia: Conway’s Game of Life

- rust

- crates: